Show Function is Continuous at Point Multivariable

Multivariable calculus (also known as multivariate calculus) is the extension of calculus in one variable to calculus with functions of several variables: the differentiation and integration of functions involving several variables, rather than just one.[1]

Multivariable calculus may be thought of as an elementary part of advanced calculus. For advanced calculus, see calculus on Euclidean space.

Typical operations [edit]

Limits and continuity [edit]

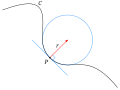

A study of limits and continuity in multivariable calculus yields many counterintuitive results not demonstrated by single-variable functions.[1] : 19–22 For example, there are scalar functions of two variables with points in their domain which give different limits when approached along different paths. E.g., the function.

Plot of the function f(x, y) = (x²y)/(x 4 + y 2)

approaches zero whenever the point is approached along lines through the origin ( ). However, when the origin is approached along a parabola , the function value has a limit of . Since taking different paths toward the same point yields different limit values, a general limit does not exist there.

Continuity in each argument not being sufficient for multivariate continuity can also be seen from the following example.[1] : 17–19 In particular, for a real-valued function with two real-valued parameters, , continuity of in for fixed and continuity of in for fixed does not imply continuity of .

Consider

It is easy to verify that this function is zero by definition on the boundary and outside of the quadrangle . Furthermore, the functions defined for constant and and by

- and

are continuous. Specifically,

- for all x and y.

However, the sequence (for natural ) converges to , rendering the function as discontinuous at . Approaching the origin not along parallels to the - and -axis reveals this discontinuity.

Continuity of function composition [edit]

If is continuous at and is a single variable function continuous at then the composite function defined by is continuous at

For examples, and

Properties of continuous functions [edit]

If and are both continuous at then

(i) are continuous at

(ii) is continuous at for any constant c.

(iii) is continuous at point

(iv) is continuous at if

(v) is continuous at

Partial differentiation [edit]

The partial derivative generalizes the notion of the derivative to higher dimensions. A partial derivative of a multivariable function is a derivative with respect to one variable with all other variables held constant.[1] : 26ff

Partial derivatives may be combined in interesting ways to create more complicated expressions of the derivative. In vector calculus, the del operator ( ) is used to define the concepts of gradient, divergence, and curl in terms of partial derivatives. A matrix of partial derivatives, the Jacobian matrix, may be used to represent the derivative of a function between two spaces of arbitrary dimension. The derivative can thus be understood as a linear transformation which directly varies from point to point in the domain of the function.

Differential equations containing partial derivatives are called partial differential equations or PDEs. These equations are generally more difficult to solve than ordinary differential equations, which contain derivatives with respect to only one variable.[1] : 654ff

Multiple integration [edit]

The multiple integral expands the concept of the integral to functions of any number of variables. Double and triple integrals may be used to calculate areas and volumes of regions in the plane and in space. Fubini's theorem guarantees that a multiple integral may be evaluated as a repeated integral or iterated integral as long as the integrand is continuous throughout the domain of integration.[1] : 367ff

The surface integral and the line integral are used to integrate over curved manifolds such as surfaces and curves.

Fundamental theorem of calculus in multiple dimensions [edit]

In single-variable calculus, the fundamental theorem of calculus establishes a link between the derivative and the integral. The link between the derivative and the integral in multivariable calculus is embodied by the integral theorems of vector calculus:[1] : 543ff

- Gradient theorem

- Stokes' theorem

- Divergence theorem

- Green's theorem.

In a more advanced study of multivariable calculus, it is seen that these four theorems are specific incarnations of a more general theorem, the generalized Stokes' theorem, which applies to the integration of differential forms over manifolds.[2]

Applications and uses [edit]

Techniques of multivariable calculus are used to study many objects of interest in the material world. In particular,

| Type of functions | Applicable techniques | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Curves |  | for | Lengths of curves, line integrals, and curvature. |

| Surfaces |  | for | Areas of surfaces, surface integrals, flux through surfaces, and curvature. |

| Scalar fields |  | Maxima and minima, Lagrange multipliers, directional derivatives, level sets. | |

| Vector fields |  | Any of the operations of vector calculus including gradient, divergence, and curl. |

Multivariable calculus can be applied to analyze deterministic systems that have multiple degrees of freedom. Functions with independent variables corresponding to each of the degrees of freedom are often used to model these systems, and multivariable calculus provides tools for characterizing the system dynamics.

Multivariate calculus is used in the optimal control of continuous time dynamic systems. It is used in regression analysis to derive formulas for estimating relationships among various sets of empirical data.

Multivariable calculus is used in many fields of natural and social science and engineering to model and study high-dimensional systems that exhibit deterministic behavior. In economics, for example, consumer choice over a variety of goods, and producer choice over various inputs to use and outputs to produce, are modeled with multivariate calculus.

Non-deterministic, or stochastic systems can be studied using a different kind of mathematics, such as stochastic calculus.

See also [edit]

- List of multivariable calculus topics

- Multivariate statistics

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g Richard Courant; Fritz John (14 December 1999). Introduction to Calculus and Analysis Volume II/2. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN978-3-540-66570-0.

- ^ Spivak, Michael (1965). Calculus on Manifolds. New York: W. A. Benjamin, Inc. ISBN9780805390216.

External links [edit]

- UC Berkeley video lectures on Multivariable Calculus, Fall 2009, Professor Edward Frenkel

- MIT video lectures on Multivariable Calculus, Fall 2007

- Multivariable Calculus: A free online textbook by George Cain and James Herod

- Multivariable Calculus Online: A free online textbook by Jeff Knisley

- Multivariable Calculus – A Very Quick Review, Prof. Blair Perot, University of Massachusetts Amherst

- Multivariable Calculus, Online text by Dr. Jerry Shurman

jeanbaptistebourponshave.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multivariable_calculus

0 Response to "Show Function is Continuous at Point Multivariable"

Post a Comment